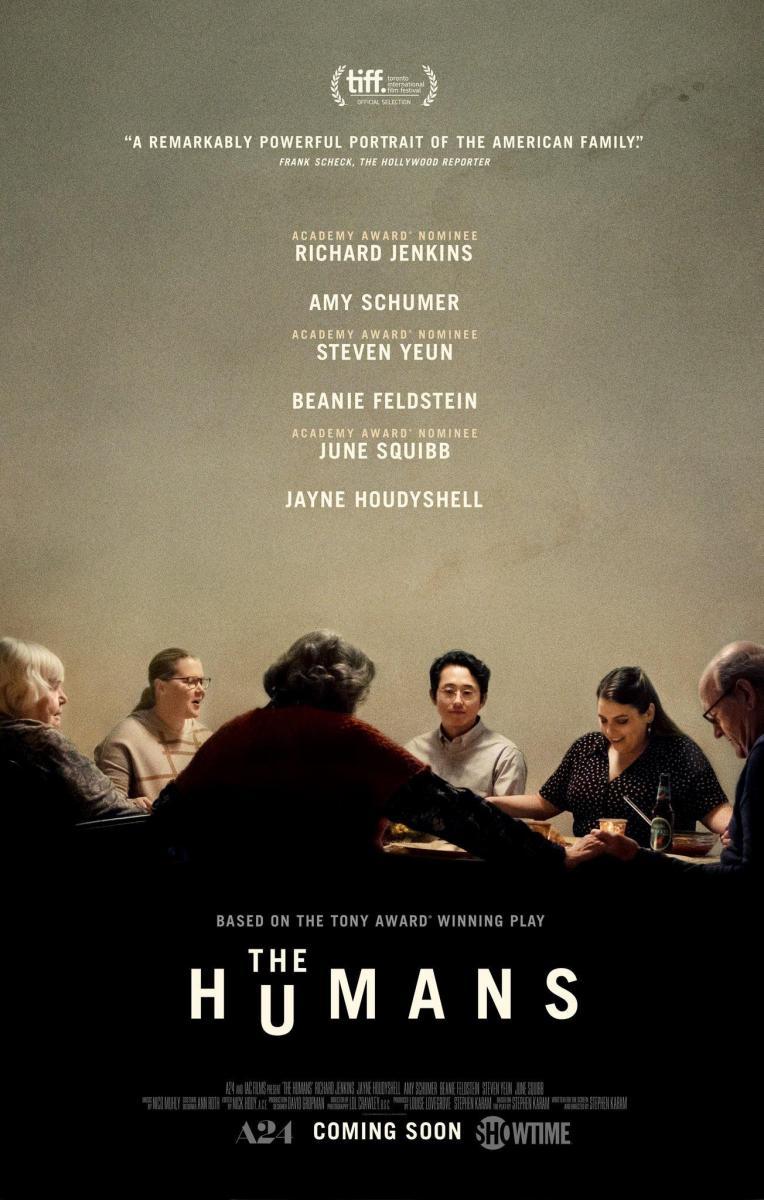

At some point earlier in the previous decade, a play appeared on the New York stage that almost immediately become something of a phenomenon. Stephen Karam’s The Humans received widespread acclaim, being seen as one of the finest achievements of the year, and celebrated as a major new entry into the canon of American literature. This is not difficult to explain – theatre has always embraced stories of family dealing with a number of issues, and Karam’s work in particular was quite strong, his depiction of a family gathered in a squalid, bare-boned New York City apartment to celebrate Thanksgiving being a fascinating character study. A few years later, The Humans has been the beneficiary of a film adaptation, written and directed by Karam himself, who takes charge of his own text and its transition to the screen. This adaptation of The Humans is mostly quite faithful, with the differences coming in the process of translating it from the stage to the screen. Every message and detail embedded in the text is brought over beautifully, turned into this brutally honest, and often quite unsettling, family drama that covers some very intimidating narrative territory under the guise of commenting on a range of deeper issues that are not necessarily contained to this family themselves, but rather indicative of a broad spectrum of difficult conversations that have dominated American (and global) culture for the past two decades. Beautifully composed, but in a way that is consistently drawing our attention to the more bleak realities that are faced by several individuals, many of whom are represented in the characters present throughout this film, which serves as both a fascinating character-based text, and a terrifying testament to the bleaker side of the human condition.

It’s not a revolutionary observation, since one merely has to spend a few minutes with the characters in this film to realize that The Humans is functioning as a horror film in all aspects outside of the actual tangible elements that define the genre. While it may be difficult to tell based on the premise, which implies that Karam’s text is a brooding familial drama about concealed secrets and broken promises, there’s a forthright sense of foreboding danger that lingers over the film. However, the plot doesn’t conceal any surprises (outside of a few minor revelations used to develop the characters), the entire film being constructed as an unconventional horror film that draws terror from the most ordinary scenarios. It has all the qualities of a traditional haunted house narrative, taking place in a single space, the various nooks and crannies harbouring deep secrets that are drawn from memories. There is nothing quite as terrifying as the spectre of the past, which haunts these characters as they revisit moments from their own lives that they often play off as inconsequential, but have clearly impacted them. Karam’s decision to design The Humans as a film that may lack actual terror in terms of a legitimate supernatural presence that traverses that small apartment, but rather one where the ghost is that of the past, which becomes increasingly hostile the more the characters allow it in. It takes the form of a faceless woman that appears in the dreams of the family’s patriarch, and what starts as an amusing anecdote that is the source of a lot of laughter for his fellow dinner guests eventually becomes the driving force behind the film, whereby the director plucks some very complex discussions around the concept of trauma out of these characters and how they react to a tangible feeling of dread, which both unites them, and ultimately drives them apart, leading to the harrowing final scene that is, without question, the most frightening and challenging moment out of any film in the past year.

The inherent obstacle that comes with adapting a play to film is that the process of transitioning it from stage to screen is often too overly simplistic, with most resorting to filming the play in a slightly larger set, rather than having it performed on stage. Karam being placed at the helm of this adaptation didn’t do much to assuage these concerns, since putting the creative mind behind the stage show in charge of the adaptation would likely result in the same process, especially when it is his directorial debut as a film director. The Humans interestingly doesn’t ever fall into this same pattern of unconvincing adaptations, which is doubly impressive considering how this is designed to take place in a single location. The director does well in expanding this adaptation beyond the “six people talk at a table” trope that many theatre dissidents will doubtlessly mention, turning The Humans into a film that is motivated by tone more than anything else. Karam sets a particular mood throughout the film – it starts as a melancholy, vaguely charming family drama, where the past few months in each character’s life is mentioned through the traditional catching up that occurs at such gatherings – and then it gradually transitions into darker narrative territory, especially in the process of the characters revealing more worrying secrets, whether it be through directly addressing them, or in the form of implication, which slowly sets off an entirely new series of conversations that complicate the interpersonal relationships. It can sometimes feel quite overwhelming, especially since there is a gradually encroaching sense of despair that reaches a haunting crescendo by the end of the film, which is likely to leave even the most stone-faced viewers in something of an angst-filled panic, if not a full existential crisis, as Karam hands over the proverbial keys to these characters and their trauma, inviting us to insert ourselves into their world, and explore our own trauma. The moment that table goes from being the location of a friendly family dinner, to a seance used to evoke the spirit of the past, we understand exactly how the director intended to find horror in the urbane and modern spaces.

Karam is also a director that proves himself to be keenly aware of space, which is likely a result of his work in the theatre, which has clearly motivated some of the directorial decisions in this film. The Humans is a film about characters interacting over the course of a single day, and the apartment in which it takes place becomes a character on its own, as does the building as a whole. The creaking floorboards and random thuds create an aural landscape that works in conjunction with the restrictive nature of the apartment, which may be quite small, but is designed in such a way that it feels almost infinite. Corridors appear endless, some rooms and corners go entirely unexplored, and there is a general mystery that persists throughout the film that comes about through Karam’s approach to representing space. It’s a slightly more avant-garde approach, and our attention is constantly drawn to how these actors navigate the space, the methods taken by the cast in developing these characters in relation to their surroundings. It’s almost as if none of these people leave that apartment the same as they were when they entered – shocking revelations cause them to re-evaluate not only what they thought was true about their fellow family members, but also their own understanding of the world. Using the apartment as a backdrop for these discoveries and existential ponderings is an effective way of allowing it to emerge organically – and not once does it feel like Karam is resorting to depending on the stage-bound origins of the work. Instead, he expands the world of The Humans, transforming it into an environment that is both terrifying and evocative, and the fact that he does so through the most simple means, whether it be the bare production design or the use of lighting (another very strong component of the film), we find ourselves easily getting lost in this world.

The characters are logically the primary driving force behind The Humans, which depends mainly on the actors put in charge of these roles. Interestingly, despite having some tremendously talented actors in the cast, not a single one of them is a standout. There are six primary characters, and they are all of equal importance – no one is ever given the spotlight more than another, and in turn manage to support each other genuinely, working with their fellow actor to take on these roles. Richard Jenkins is the family’s patriarch, while Jayne Houdyshell (reprising her celebrated performance from the Broadway stage show, which she originated through its run) is his wife – and presiding over this family, they’re both fiercely dedicated to the roles, using their decades of experience to play these individuals, who may be older, but still contain a ferocity that makes them formidable opponents for their children, who simply see them as their parents, rather than fully-formed individuals. Amy Schumer makes a decent entry into more dramatic work as the older of the two daughters, a chronically ill woman who has lost her girlfriend and is soon expected to lose her job, while Beanie Feldstein (who is gradually transitioning into being one of our finest young actresses) is the film’s anchor, the character who facilitates the entire story by being the host of the dinner party covered in the film. In the periphery are the wonderful June Squibb, who once again proves her brilliance as a great character actress in the part of the disease-riddled grandmother whose very presence evokes a lot of discussions, and Steven Yeun, who is as genial as ever as the charming fiance to Feldstein’s character. The Humans is a true ensemble effort, and much like the rest of the film, Karam uses his cast as a tool to explore this story, and whether viewing them as a homogenous entity, or following their explorations of space, it becomes quite a profound piece on its own in terms of the performances.

The adage normally associated with such narratives is that “misery loves family”, which was used most prominently in another celebrated stage play, August: Osage County, which serves as something of a more upbeat relative of this story, the pastoral dark comedy being replaced with urbane horror, but still featuring the same approach to family-oriented drama, and the gradual revelation of earth-shattering secrets. The Humans is a supremely challenging film, and not always a pleasant experience, but one that has a sense of robust debate. It’s a film that designs itself along the lines of horror, while never actually featuring the components we’d normally expect from the genre – the encroaching danger comes from within these characters, who shockingly discover that, regardless of where they currently exist, both physically and mentally, there is a burden of the past that weighs upon them. Whether it is a kind of pressure from their familial legacy, where dark secrets of their shared past begin to appear, or their challenges drawn from their everyday lives, each one of these characters is dealing with their existential quandaries – and when placed together in a confined space, which gradually becomes more unnavigable as time moves on, the true horrors being to manifest, leading to a shocking and often quite unsettling representation of this family dynamic, and the people who are involved in it. It’s a stunningly beautiful film in terms of technical prowess, with Karam’s ability to derive terror from something as simple as Thanksgiving dinner being primary to his exploration of the human condition, and the angst that comes about as a result of realizing one’s own inability to fully comprehend his mysterious world, which none of these characters seems capable of recognizing. It’s a daring, thought-provoking work with a lot of unexplored territories, which is where Karam encourages us to enter into this world, allowing the viewer to assert their own understanding of these themes, evolving into a bold and evocative drama that manages to be more unsettling than any of the more traditional horror films of recent years.

On Saturday night October 13, 1962, a new play premiered on Broadway. Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? shattered many silent rules of the commercial theater. The production was a lengthy sit at three hours, the script freely incorporated profanity, and the single set show was four characters swilling copious amounts of alcohol as the drunken stupor allow secrets to be revealed. The play was a smash, winning numerous prizes and sell out crowds. In 70 years since, the premise of a group of people dispelling illusion and revealing their truths has been beaten into the ground. The Humans is merely the most recent Broadway show to borrow this structure.

Here we meet the Blake family who have gathered for a holiday meal in the decrepit New York apartment of their daughter and her lover. The family is struggling with various health crises, economic woes, and the erosion of faith (religious). During the course of the holiday meal, emotions will be strained, feelings wounded and secrets revealed. Sadly, while the actors try very hard to make all of this feel significant, it isn’t. The money woes are dictated by poor planning decades earlier, the wounds are mostly superficial and typical of situations where adult children are asserting independence, and the shocking secrets are rather pedestrian. Playwright Stephen Karam’s efforts to elevate the limp story with allusions to horror in the set design is more manipulative than intriguing. A disappointment.